In July, the Global Footprint Network released its annual estimate of Earth Overshoot Day – the date on the calendar in which humanity’s ecological footprint (demand for nature’s services) exceeds the planet’s biocapacity (the amount of resources the Earth can generate in that year).

Earth Overshoot Day has been on a steady march forward for decades (from December 29th in 1971 to September 16th in 2000 to August 4th in 2015), and this year fell on July 24th.

Thus, we are consuming the Earth’s natural services at a rate of 1.8 planets as opposed to the one that we have and need to protect.

The Global Footprint Network aptly refers to Earth Overshoot as humanity’s largest market failure, because business operations do not internalize the costs that they impose on natural systems.

There is a significant cost to overshoot, of course. It is an inherently unsustainable condition, and it shows up in the form of record heat, droughts, massive wildfires, intense storms and flooding, depleted fish stocks, excessive plastic pollution, ocean warming, melting sea ice, and more.

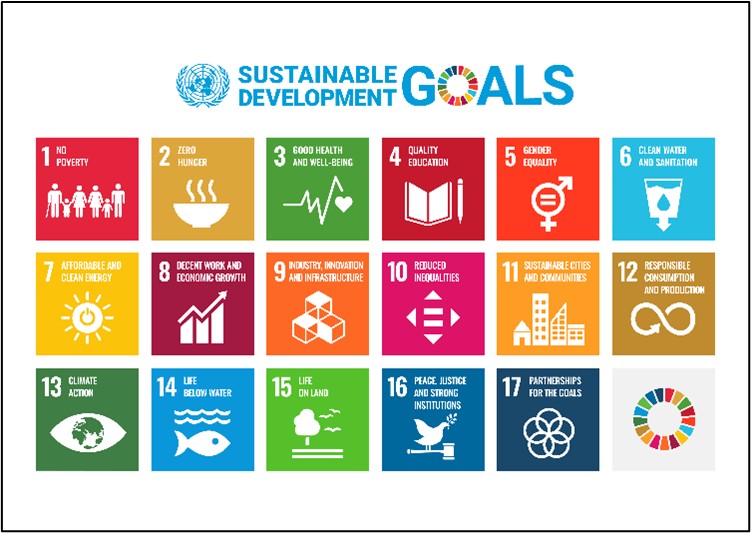

Increasingly, each of us can see and feel these impacts in very real terms, and yet collectively we still aren’t acting with the required speed to address the drivers, which lie at the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals.

For example, the UN’s recent 2025 progress report on the SDGs notes that just a third of SDG targets are on track or making moderate progress, while about half are moving too slowly, and nearly one quarter are in reverse.

Similarly, we are beginning to hear more about research on the planetary boundaries framework – a 2023 report (Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries) finds that six of the nine planetary boundaries have been transgressed, and that “humanity is today placing unprecedented pressure on Earth system” with the result that Earth is in danger of leaving its current Holocene-like state.

Significantly, co-author Johan Rockstrom pointed to concerns of “rising signs of dwindling planetary resilience” which bring us closer to irreversible tipping points.

But here too we haven’t begun to take global action at a level commensurate with the severity of these threats.

Connecting planetary health and human health

And we now must quickly place greater focus on the linkage between planetary health and human health.

A new paper in The Lancet (Connecting planetary boundaries and planetary health: a resilient and stable Earth system is crucial for human health) makes that critical connection, noting that “destabilizing the Earth system is fundamentally threatening human health.”

The authors warn of a large global health burden in the coming decades from environmental degradation. They also note that “justice is central for safeguarding health within planetary boundaries,” reminding us that the health effects of environmental decline disproportionately affect Indigenous peoples, low-income regions and marginalized populations, and future generations (those who bear the least responsibility for the decline).

Paul Polman cited this research in an excellent post (Sicker Planet, Sicker People: Environmental breakdown is eroding the foundations of human health) in which he raised the alarm regarding the connection between environmental degradation and human health.

Polman didn’t mince words in educating us on this critical connection, noting that “Land degradation and biodiversity loss are fueling outbreaks of malaria, dengue, and other zoonotic diseases. Chemical and plastic pollution is driving development delays, hormonal disruption, and soaring rates of anxiety and depression. Rising temperatures are linked to pregnancy complications, kidney failure and mortality spikes.”

He cited our tendency to discuss planetary boundaries in abstract terms, powerfully adding that “The true costs of planetary boundaries are not found in charts. They are found in neonatal units and cancer registries, in stolen potential, and in the quiet grief of families facing wholly preventable illnesses and deaths.”

He elevated the human element and made the connection between environmental degradation and declining human health personal – which (as noted in last month’s post) is what we must do to galvanize collective action for sustainable transformation at all levels of society.

New (and greater) challenges, new leadership needed

It is clear that we are in need of new leadership across all levels (business, government, education, NGOs, and even individuals) to advance sustainable transformations in critical systems, especially food and energy, which produce such strong externalities.

Leaders who can break established, linear operating paradigms that accept high levels of waste, emissions, pollution and inequity and instead unite organizations and countries in sustainable, regenerative, and equitable transformations of critical systems to meet planetary and human health needs.

Leaders who can make sustainability a core part of business strategy and push actions and expectations through supply chains for far greater impact.

Leaders who can implement responsible policies and regulations to reverse negative environmental impacts and benefit all.

Leaders who are positive disruptors; authentic, inspirational, transformational, collaborative, and above all, humanity-focused.

In short, we are in need of next-level leaders for sustainable transformation.

Polman gives a useful framing for the new leadership needed to address the challenges of planetary boundaries, calling for “a wholesale upgrade to the operating system of modern leadership.”

That’s an excellent starting point.

And I think it should be applied to all levels of society.

Getting on the right side of history

On that score, we can draw leadership lessons from another excellent piece by Inger Andersen of UNEP.

in a 2021 speech entitled Sustainability is about being on the right side of history, Andersen outlined the case for all of us to be changemakers in the effort to “transform our societies so they operate in harmony with nature.”

She began by outlining the depth and scale of three planetary crises – climate change, nature and biodiversity loss, and pollution and waste – noting that all three stem from unsustainable consumption and production.

Andersen pointed out several steps that governments can take to lead sustainable transformation, but importantly, she warned that we can’t leave the responsibility for solving these challenges with governments alone.

Further, she called for “whole-of-society action for a whole-of-society problem” and noted that “we all need to take responsibility” for leading sustainable change “in every aspect of our work and professional lives.”

She made an additional brilliant point in recognizing the daunting and intangible nature of sustainability challenges that can lead to feelings of helplessness and inaction among individuals (something that I hear from my students), advising that “it can be difficult to make sustainable choices in a system that doesn’t encourage them” but “we all need to try.”

I completely agree. This is a core element of what I teach in my food system change-focused graduate classes – getting students to grasp the scope and impact of these major sustainability challenges, the drivers behind them, the linkage between them, and the imperative to take urgent action in our work, academic, social, and family circles.

In a call out to business leaders, Andersen also addressed the business case, noting that sustainability is in their best interest, not only because of the threats of climate change and nature loss to business profitability, but because of the growing expectation among consumers that they will act responsibly.

In other words, sustainability is smart business.

Specific to food system change, Paul Polman made a similar case at the 2021 UN Food Systems Pre-Summit in Rome, stating that “It is impossible to achieve the Paris Agreement on climate or the Sustainable Development Goals if we don’t drastically change the food system. And the most interesting thing is, that of all of the options we’ve looked at in any part of the Sustainable Development Goals, this probably has the highest return, from an ecological, from a social, as well as from a financial perspective.”

He added that “With our own existence being put at risk, with enormously attractive economics, it’s just mind-boggling to me that we’re not moving faster.”

We are in need of business leaders who can make that connection and move faster on food system transformation.

Andersen called on business leaders to account for the value of nature in operations, and to set science-based targets for nature, climate, and pollution. Further, she called on them to push sustainability through their supply chains by holding suppliers responsible for similar standards, and report transparently on action and progress.

She also called on students to be the changemakers in organizations – challenging existing actions and culture and providing a moral compass.

Last, she asked all of us as individuals to make sustainable choices in all that we do – transportation, food, fashion, etc.

Both Polman and Andersen have provided valuable lessons here.

The gravity and scale of the sustainability challenges we face requires 1) a “wholesale upgrade” to how business leaders view and act on sustainability challenges, and 2) a whole-of-society approach to solving these challenges with urgency.

We will all need to guide the development of next-level leaders to put humanity first and orient their organizations to contributing positively (not negatively) to issues of environmental health, human health, and planetary boundaries.

We will all need to act as sustainability leaders to overcome humanity’s market failure and get on the right side of history.

(Note: I’ll be speaking on these topics at the Food Days conference in Seinajoki in September with an emphasis on leadership for food system change, and this research will continue).